Professional Experience

KPMG

At KPMG, I quickly assumed a technical leadership role, guiding various projects

as we modernised our clients' sales platforms, implemented automation for providing data insights,

and streamlined their high-frequency processes. I prepare devops pipelines, conduct code reviews,

and undertake significant pieces of the development work myself.

If you visit lululemon's website today, you can interact with a generative AI agent that can

help you process your return, track your shipment, or update your account details. I helped

build that! Perhaps the most complex work I did here, however, was designing and

developing a highly customised security framework for CIBC that operated

in real time and under load. An entire division of bankers log in every day and see

exactly the data they're supposed to see, and no more, thanks to that solution.

Moonlight Haptics

At Moonlight Haptics, we built a device to allow someone with visual impairment to

“see” using their sense of touch. In our backyard, we produced an electronic display

from scratch, then replaced the pixels with vibrating motors. The intensity of the vibrations

corresponded to the distance of the perceived objects, and it was precise enough to distinguish a

difference of 10 cm, 1 m away, with 90% accuracy.

What I accomplished at Moonlight Haptics has been among my most extraordinary work.

You can see below a demo of the lightning-fast rescaling algorithm that feeds to the physical

display in real-time, complete with a no-look high five at the end.

Lumentum

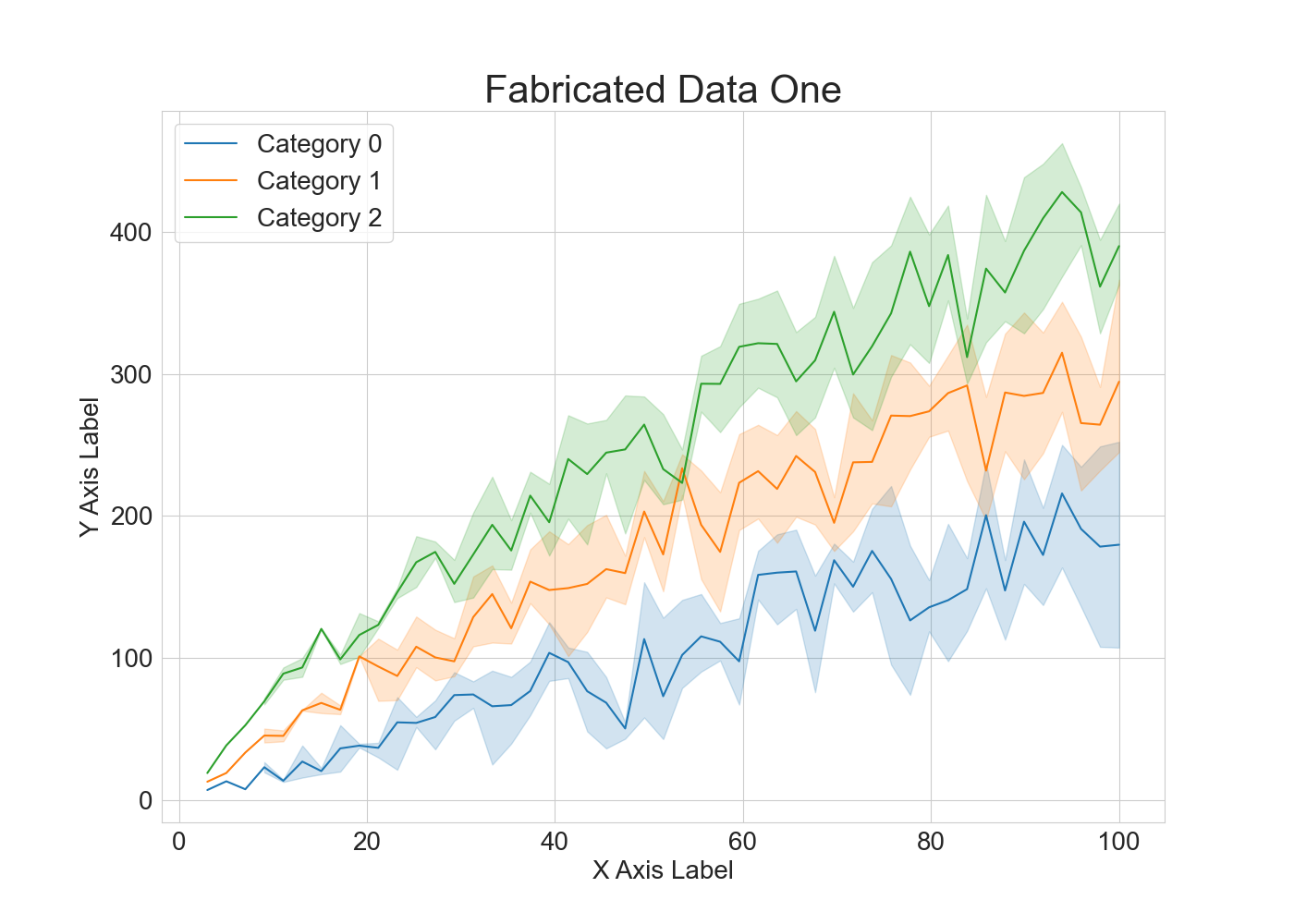

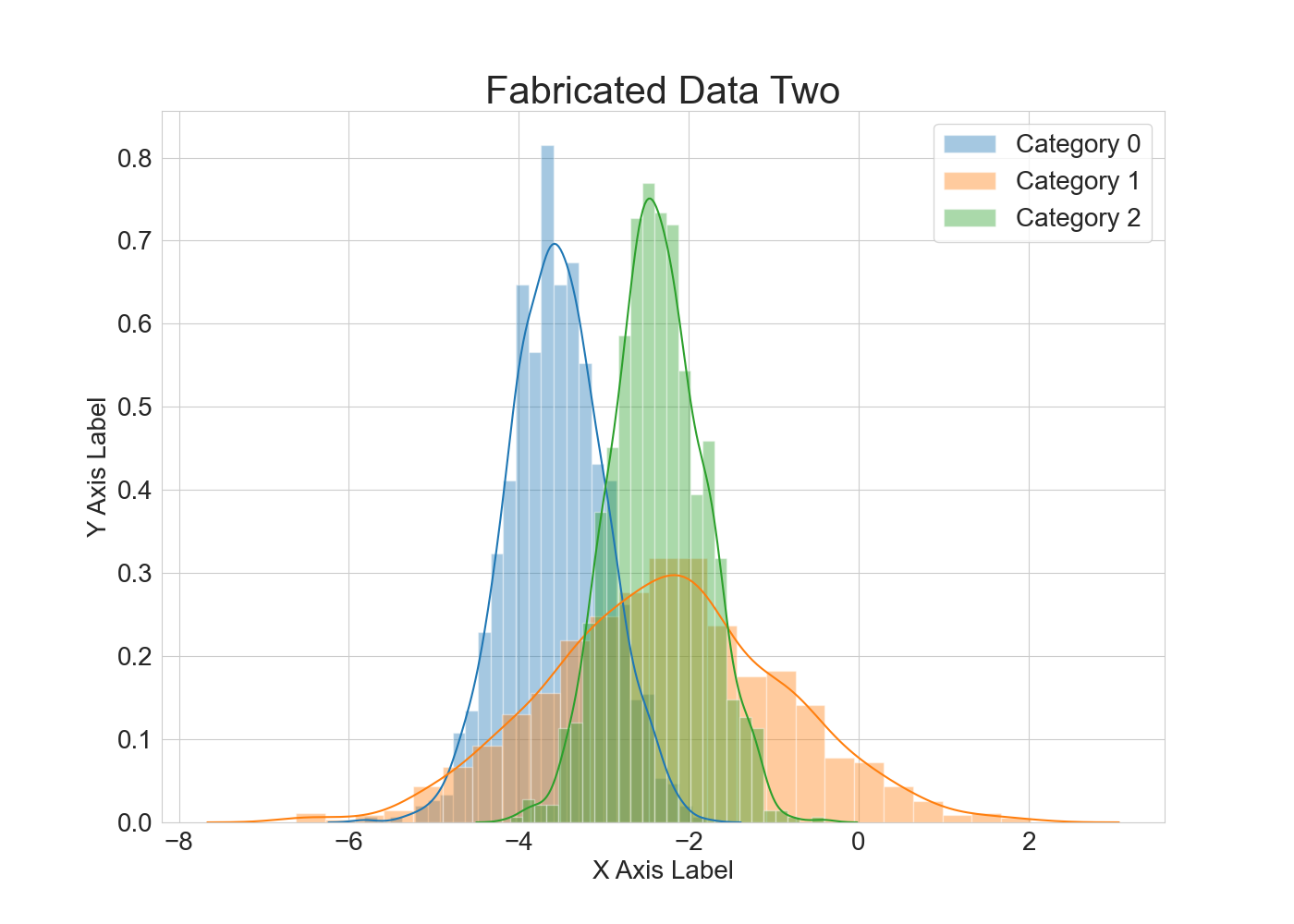

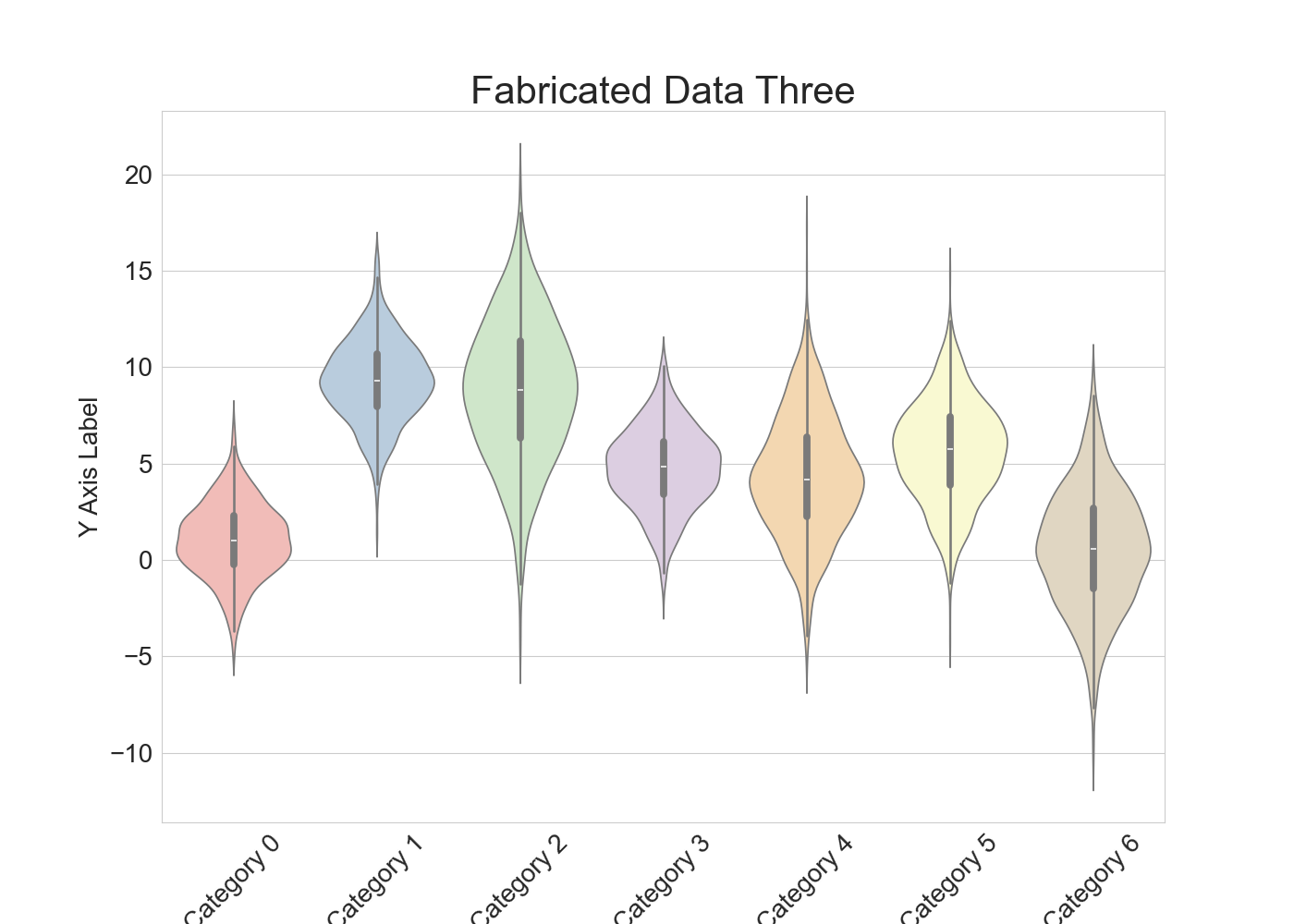

As a data scientist, I queried big data, cleaned it, then produced hundreds of

visualisations and analyses catered for each of the teams throughout R&D. I built regression models,

conducted statistical analysis, and improved manufacturing efficiency and yield. I was particularly

adept at automating large swathes of my work to push projects faster while maintaining the

high-quality outputs I was known for.

My work also had the potential to be a single point of failure for projects involving the

company's biggest customers — it was quite a lot of responsibility!

Princeton University

Qubits, naturally, are most famous from the world of quantum computing — you may have

seen the intricate golden machines built at IBM or Google, but these computers operate at

temperatures colder than outer space. The qubits I worked with at Princeton were

room-temperature, which is one of the reasons they could be used to precisely locate and

identify individual atoms of biological molecules that would otherwise freeze.

Although engrossed deeply in the world of physics here, I was no theorist. I was, however,

able to write hyper-efficient code to conduct tens of billions of automated experiments in a

matter of months, then generate insights that let us learn much about how our qubits interacted

with each other and their environment. This led to my co-authorship on a paper which we later

published to PRX Quantum.

Halion Displays

Your colour printer, if you've ever noticed, has three ink colours: cyan, magenta, and yellow

(and often black as a fourth). Mixing them in different amounts produces any desired colour

on the page. But what if you could make an ink that changes between those three colours when

you give it an electric signal? It would allow you to make the screen on your mobile device look

like ink on paper while it plays video. It would be gentle on the eyes at night and vibrant

outside in direct sunlight.

Working at Halion Displays was what inspired me to eventually pursue Moonlight Haptics a few

years later. The goal is brutally difficult to reach, you're forced to push the limits of

human knowledge in disparate fields you were never qualified to pursue in the first place, but

there's a small chance you can make something that can really change our lives for the better, that

only you were brave enough to try.